Trump’s claims that U.S. students have been brainwashed is totally true – just not in the way he meant. Rather than being brainwashed “to hate our country,” we’ve been brainwashed to learn only the positives about our history, or in the rare cases where negatives are widely known, such as the racist internment of Japanese citizens during World War II, they are presented as “mistakes” that were eventually made right (with a 1988 apology and $20,000 to each surviving internee).

An incident in one of my first classes at the University of Wisconsin in 1967 left an indelible mark on my brain, and perhaps contributed to my decision to major in history. The professor was talking about the early days of the new U.S. government when there were only four cabinet positions: Secretary of State, Secretary of War, Secretary of the Treasury and the Attorney General. He said State dealt with relations with other sovereign nations, except for indigenous tribes, which were handled under the War Department. I asked (with some trepidation about speaking up in class) why the native nations were under the War Department and not the State Department. I don’t remember his answer; I just remember how defensive his reaction was.

Since then I have supplemented any official readings with my own explorations – and yes, those have often been much more critical of the U.S. Trump specifically called out Howard Zinn and his “People’s History of the United States,” published in 1980, which tells many of these little-known stories. Interviewed by Amy Goodman on Democracy Now, Zinn said it was important to tell young people the truth. The reasons so many of these books and podcasts sound so negative is that they are countering the rosy picture most of us have been indoctrinated with.

I’ve read a lot of women’s history, but I learned more in this centennial year of the Nineteenth Amendment, which is usually described as “granting women the right to vote.” That doesn’t quite capture the more than 70-year battle women (and sometimes their male supporters) waged to win that right, especially toward the end when women were beaten, arrested and force-fed in jail. This year I also learned more about the role of black women suffragists, who were most often excluded or put at the equivalent of the back of the bus in white-led suffrage demonstrations.

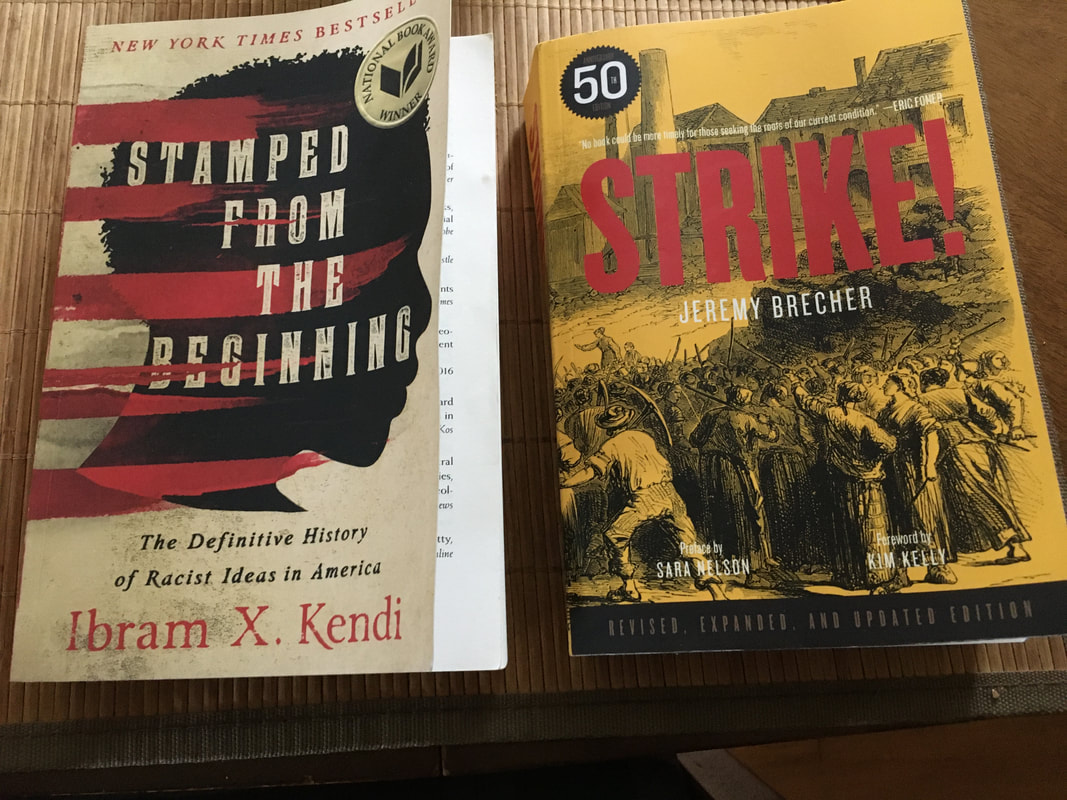

I just finished reading “Stamped from the Beginning: The Definitive History of Racist Ideas in America,” by Ibram X. Kendi, the National Book Award winner published in 2016. Broken into five parts, headlined by Puritan leader Cotton Mather, slaveholder Thomas Jefferson, abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison, African American scholar and political activist W.E.B. Dubois, and radical Black activist Angela Davis, Kendi interprets the various epochs by their adherence to the concepts of Segregationist (Blacks are sub-human), Assimilationist (Blacks can aspire to be as good as whites) and Anti-Racist (Blacks are already equal to whites).

I never read Jeremy Brecher’s “Strike!” when it was first published in 1972, but I’m making my way through the 506-page, updated 50th anniversary edition of U.S. labor history, published this year. I already knew the high points, like the Haymarket massacre, and the fights to organize in the coal fields, the steel mills and the railroads. But I learned a lot about more recent history, like the wave of strikes during the Vietnam War era, when I was busy protesting on campus. The fact that I was alive in this period, and fairly conscious of social struggles, yet knew nothing about this, is another indication of my mis-education.

The other key element in my re-education, besides just learning these facts, is that I read/hear/see these fighters for a more inclusive, still far from perfect democracy in their own words. Kendi is an African American historian, and Brecher gives us long excerpts of everyday workers describing their desperate living situations that pushed them into action, as well as riveting stories of the strikes they engaged in to improve their lot. Some excellent documentaries about the struggle for women’s enfranchisement this year included recitations of their public writings and personal journals.

The “great man” (read white, powerful, and, of course, male) theory of history has filled our textbooks for centuries. It’s time to turn to the stories of “regular people” and the oppressed and exploited for a fuller picture.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed