I was part of the Rocking Chair Rebellion, a group of 10 elders (and one young supporter) who traveled to Atlanta during the Week of Action Against Cop City, when the local opposition to a militarized police training facility called for support against an increasingly violent police response and increasingly heavy-handed legal ramifications. Forest defender Tortuguita was killed by police on Jan. 18 (see my previous post here), and 19 protesters had already been charged with domestic terrorism – a felony calling for up to 35 years in prison – when the specific “crimes” they’d been charged with were no more than trespassing or sitting in trees.

When we gathered Sunday evening at our AirBnB to finalize our plans, we didn’t know that police at that very hour had again raided the forest while a music festival was going on with hundreds of attendees, including children. The raid was apparently in response to a smaller group of camouflaged protesters who destroyed some equipment and threw projectiles at the police at another site in the forest; 23 more people were charged with domestic terrorism, most of whom had nothing to do with that action. Since almost all the arrestees are from out of state, they were denied bail because they have “no local ties,” even though local organizers had invited people to come down to be in solidarity.

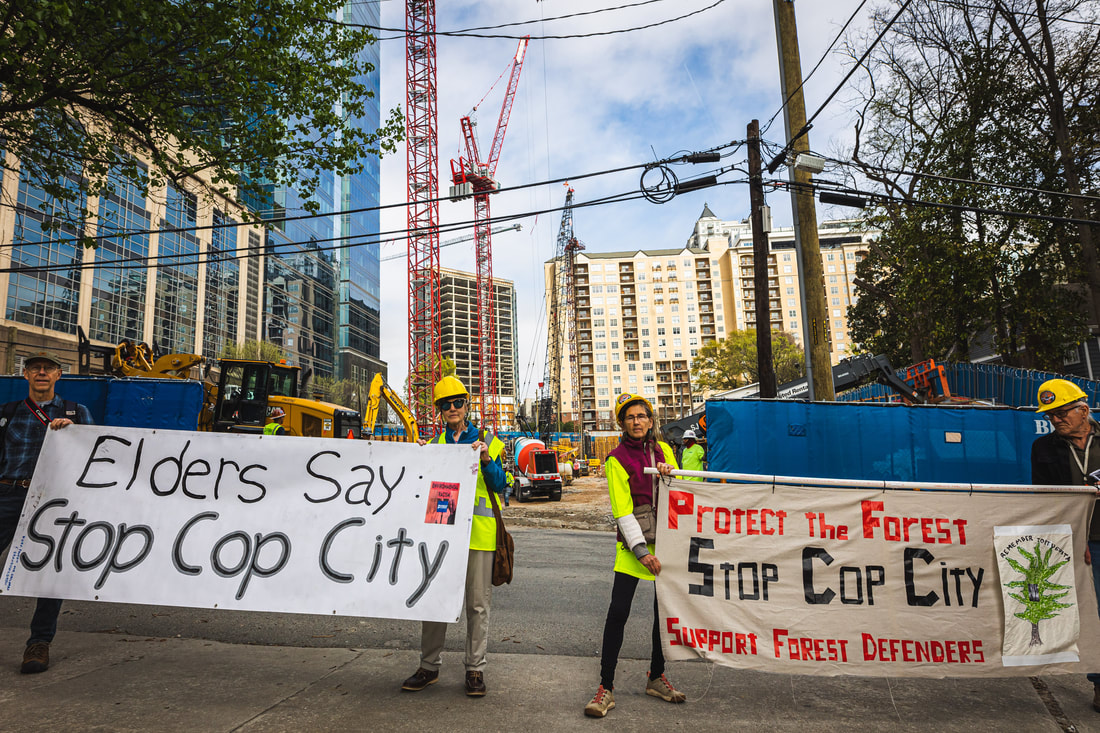

The next day, Monday, we visited the Atlanta headquarters of Brasfield & Gorrie, the general contractor for Cop City, and five of its other construction sites around Atlanta. We held banners, passed out flyers and otherwise let the company know that we want to Stop Cop City and Let Atlanta Breathe. (That's me in photo below, holding the left banner, wearing a hard hat.) Our main purpose was to show that it’s not just young people who are opposed to this project, whose official name is the Atlanta Public Safety Training Center. Plans include shooting ranges, roads for high-speed chases, a mock town to practice urban warfare, and a Black Hawk helicopter landing pad, all to be built on 85 acres in the middle of the South Atlanta Forest, that was the former site of a prison farm and was land the Muscogee Creek indigenous residents called Weelaunee before they were expelled almost 200 years ago on the Trail of Tears. A group of Muscogee arrived from Oklahoma on Wednesday to deliver an expulsion order to Atlanta Mayor Andre Dickens and demand that the land be returned to them.

Our flyers said Cop City would increase the use of militarized policing of the already overpoliced Black and brown neighborhoods adjacent to the site; destroy acres of trees, which are badly needed to reduce the flooding that already occurs in local communities, to clean the air where residents already suffer from high asthma rates, and to reduce the urban heat island effect; exacerbate climate change, and greatly increase noise and particulate pollution. We added that Nature has its own right to exist, and provides beauty and tranquility for humans and other living things; and that the City of Atlanta could find much better uses for the $30 million it has promised toward building this $90 million facility, like funding non-police responses to improve security and improving health care for its most at-risk residents.

Our efforts reached thousands of motorists, pedestrians and construction workers with information about the project, and we were only threatened with arrest once. We felt like it was a small but useful contribution.

The majority of our group departed on Tuesday, but I stuck around with a few others to participate in two actions in downtown Atlanta. One was a march to various corporate supporters of the Atlanta Police Foundation (APF), which is the private entity behind Cop City, investing $60 million into the project.

There were fewer than a hundred marchers, and it seemed like more cops than protesters. They were decked out in riot gear, many carrying long guns, some of which were loaded with pepper balls. They had an honest-to-god tank parked nearby. They seemed to be on all sides of us and were very intimidating; we were afraid of getting kettled and arrested (and who knows what else). I couldn’t afford to get arrested just then due to an important upcoming commitment, so I peeled off and kept a little distance, when I ran into some young people who had done the same. Then I had some of the most interesting conversations I’ve had about being in the movement. They asked me how I decided what level of risk to take, and I found myself telling them that elders – who are retired, have no kids or parents to care for, and don’t have to worry about a criminal record getting them fired from a job or unable to get a job – have the least to lose but often are more conservative than the young ones who have everything to lose. They are leading with their anger and their love and we must support them!

Later that day we finally got to see the forest. We got a tour from someone staying there, and walked among dozens of tents where young people had re-occupied the forest after everyone had been cleared out on Sunday. There were cooking and washing stations and lots of literature available at the welcome table in the parking lot. It was a beautiful day and the forest was lovely and serene.

Although 70 percent of the people who testified at a 17-hour public hearing two years ago were against Cop City, it’s unclear to me how that translates to the general population; most of the people we encountered said they knew nothing about the actual plan, and a few were in support.

In addition to Cop City, there is a plan to consume many more acres of forest to build a film production studio. All this construction would be in direct contradiction to a plan adopted about six years ago to conserve the forest – called the fourth lung of Atlanta – as passive recreational space, where the trees would not only clean the air for a mostly Black neighborhood adjacent to it where families already suffer high rates of asthma, but reduce flooding and help mitigate climate change. By the way, the weather was unseasonably warm while we were there, with highs in early March around 80 on Monday and Tuesday.

Stop Cop Stop is a leaderless – or leader-full – movement promoting independent action and diversity of tactics. The mantra is, Don’t do anything you don’t want to do, and don’t criticize what others do. That was crystalized for me when I met a young woman who’d been at the music festival Sunday night. “We weren’t expecting” the police response, she said. I said something like, “I guess only the people destroying the equipment expected it,” and she responded, completely non-judgmentally, “We may have different approaches, but we all have the same goal.”

Opponents of Cop City posit that this type of militant action likely caused the first general contractor (before Brasfield & Gorrie) to quit, and has kept the project from moving forward so far in any significant way. They may very well be right.

I met a lot of brave young people and local, especially African American, residents who are defending the forest and calling for the end of Cop City as if their lives depend on it. In some ways, they do -- it's the campaigns against environmental racism, police abuse and climate change all in one package. We can learn a lot from what feels like a watershed struggle for environmental, climate and racial justice.

Click here, here, and here for past interviews and background about Stop Cop City, including one from the Week of Action, and here for an update on Tortuguita's killing after an independent autopsy showed he was likely in a cross-legged sitting position with his hands raised when he was shot. The press conference featuring their parents, brother and the family's attorneys starts around 6:30 in the video. Visit here to learn more and take action: donate to the Atlanta Solidarity Fund, email or call local politicians and the corporations funding the Atlanta Police Foundation.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed