When we take nonviolent direct action to protest construction of horrors like methane gas pipelines or LNG (liquefied natural gas) export terminals, we are often arrested, usually charged with trespassing or obstructing an officer, or in some states like West Virginia, violation of the critical infrastructure law. The charges are usually bargained down to a fine and/or community service, or if we choose to go to trial, they usually end up being dropped (but that can require many trips to court, an onerous burden in time and money if we live far from the site of the action).

There has been an explosion of protest against the Mountain Valley pipeline, with frequent actions involving lockdowns on access roads or to the machinery used to drill this 303-mile nightmare through fragile terrain – the habitat of several endangered species, which definitely includes the human residents of these beautiful mountains.

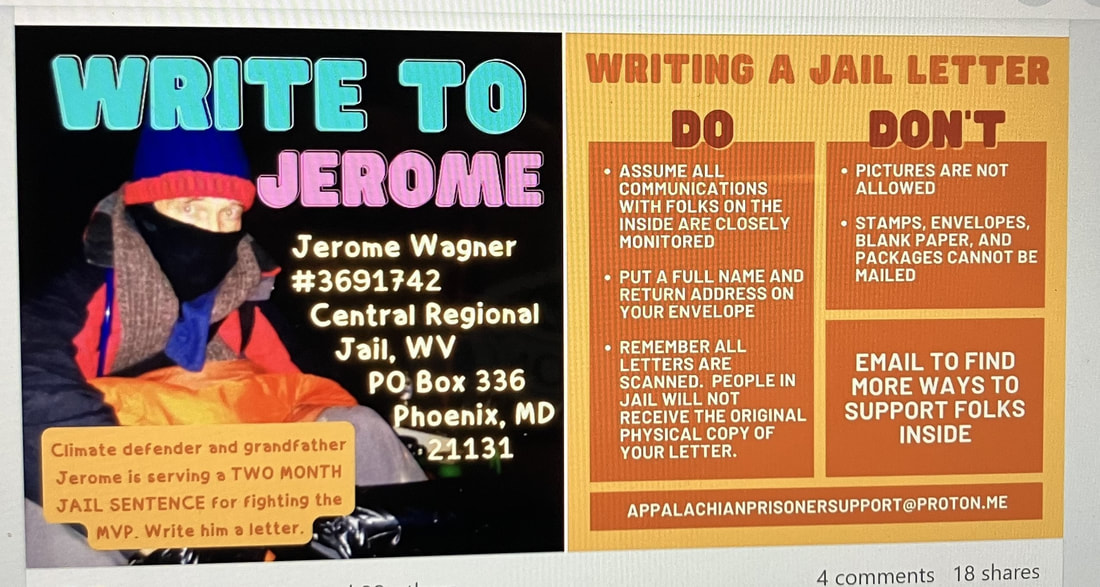

One protester who locked down to a huge drill along the pipeline route last November has experienced a different outcome. Jerome, my comrade from Beyond Extreme Energy and a grandpa living in North Carolina, is currently serving two months at the West Virginia Regional Jail. He was originally charged with five misdemeanors, all dismissed except one, and sentenced to one year in jail, with eight months suspended and serving four months with one day dismissed for good behavior for every day served – so 60 days if he stays out of trouble. The eight months suspended carries the threat of reincarceration if he violates the law anywhere in the country during that time. His release date is April 7. Jerome’s been calling me regularly to share his experience while incarcerated, so I’m turning my blog over to him. And see the graphic at the bottom for how to write to him.

===================

These are reflections of an ordinary person. I’m wondering what this all means for someone whose sentence was graver than initially expected.

I’m a privileged older white fellow who’s been successful in the “system” in terms of career, family, social involvement, etc. The environment in here is completely different. I’m in the part with misdemeanor people, not convicted felons, but still it’s different than anything I’ve experienced, and I’m not talking about race – almost everyone here is white. But everything from dental care to tattooing to what they think is funny. I’ve been called a tree hugger but without malice or scorn. That’s even though many of them are embedded in either the timber or the energy systems.

The people I’ve gotten a little personal with – three of them are involved in the gas industry and one is a logger. I was cautioned before coming in by our friends to not openly talk about shutting down work on gas pipelines because West Virginia is an energy and resource extraction sacrifice zone. But in conversations it hasn’t been negative.

Routines are very different than at home. Initially it was a scary environment; when I came into the pod – an open pod so freedom to get out and mingle – I felt like an old white guy with no tattoos. I felt like a chicken thrown to the foxes. But it’s been collegial. We help each other.

We have individual tablets; it’s a godsend. I’m calling you from inside my cell using my tablet. I charge it up in the common area and we have wifi around the pod, so I can do email with approved people, talk on the phone, order my commissary, I can access many classics in the public domain I can read or listen to, then paid apps that include games and where I compose emails. Tablets are password-protected from use by other inmates. They don’t censor outgoing mail – friends said there was no indication anything had been opened. I’m spending more time in here on screens than outside. (Note: another comrade, Andy, spent a month in jail in Montgomery County, MD, and said he had no tablet nor the kind of access Jerome has to other resources.)

We get a daily opportunity to go into what they call the Yard for 45 minutes – a cinderblock enclosure with no vegetation, a 25’ x 25’ enclosed space with cyclone fencing over the top and razor wire around the perimeter. Sometimes they give us a ball, but mostly we just walk around. If it’s sunny we stand in the sun.

The gym has a full-size basketball court divided into two. We can practice shots, run around the perimeter. There’s no gym equipment other than that.

There are three meals a day – lots of starch, carbs, very little salt, which is pretty repulsive to me; the food is overcooked, mushy pasta and rice; I’ve had no fresh fruit since I got here. For breakfast, two sausages, cream of wheat or grits, corn bread, apple juice, jelly, milk; lunch and dinner there’s dessert, which is good; dinner is mystery meat or burgers with a slice of tomato, onion, lettuce – that’s the extent of anything you would call fresh – and green beans. Meals are early and no snacking in between but we can buy our own commissary items. Some people get a specialized diet; I think they try to honor special needs.

A typical day around here is playing cards for those who like that, watching TV, walking around the common area of the pod, and sleeping. There are no work details; we’re expected to keep the cells clean and neat but that is not enforced. We’re not making license plates or breaking rocks. It’s just wasting people’s time.

There’s a counselor who takes care of routine needs. She’s fluent on using the tablet and the phone system and has helped me out. She’s also knowledgeable about jail policy and somewhat on legal matters.

I got a roommate a few weeks ago so instead of spreading my stuff all over the cell I had to consolidate. We share and talk and laugh a little bit but mostly keep to ourselves.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed